The impact of weapons technology on combat injuries forced the evolution of military medicine technology.

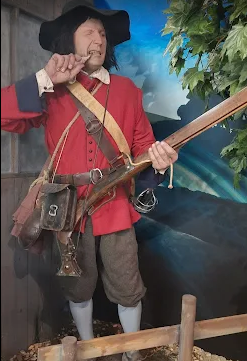

Such changes occurred over the centuries, but it was during the English Civil War when Oliver Cromwell with the Model Army repurposed a building to create the Savoy Hospital in 1642. He had realised that the previous system of camp followers tending to the wounded no longer suited with firearms causing different wounds.

David Wiggins, the curator of the Museum of Military Medicine, currently in the process of transferring from the Keogh Barracks in Ash Vale near Aldershot to be near the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, outlined the medical advances and health care since the time of Cromwell to the Probus Club of Basingstoke.

The real improvements emerged with the recognition that many combatants survived their initial surgery but died due to general conditions and disease. Regiments had their own small medical teams, but it was in the Peninsular Wars of 1808 –14 that the medical services of the army were organised on a more formal basis.

Records show that during the Crimean War 1853-56 there were 4,600 combat injuries yet 20,000 died through typhus/typhoid. Enter Florence Nightingale with her disciplined approach to medical care that started a reversal of such statistics so that during the Boer War 1899-1902 with 22,000 wounded that a reduced percentage of 7,400 died from dysentery or typhoid fever.

The industrial scale of WW1 1914-18 brought in new wounds due to advances in military equipment. There was an equalisation between combat deaths and disease and a recognition that it was imperative to remove casualties from the battlefield to proper recovery settings.

Tented casualty clearing stations then led to casualty evacuation by various methods. Motorised ambulance, some made by Thornycroft in Basingstoke converted from the order for 5,000 of their J type 3-ton vehicle, inland canal barges, hospital ships and trains.

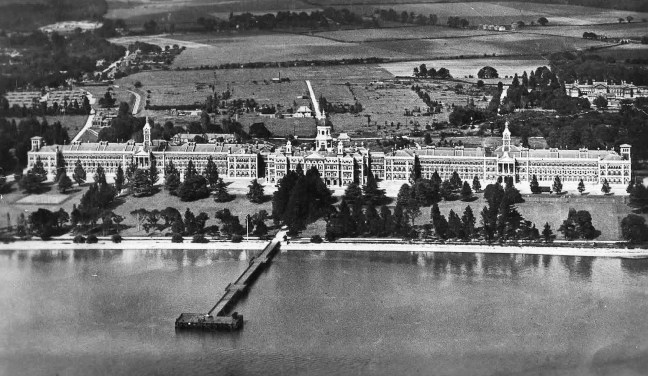

The Royal Victoria Hospital was built at Netley with its own jetty on the Solent and on a branch line ambulance trains brought casualties directly to Park Prewett hospital in Basingstoke used for Canadian troop casualties.

Blood transfusions, X-rays, gas masks for men, horses and dogs, improved designs of splints and the introduction of the Brodie steel helmet in 1916 all helped reduce deaths by 80%.

A medical officer, Harold Gillies introduced skin grafts to maxillo-facial reconstruction that became known as plastic surgery with patients at Rooksdown part of Park Prewett hospital in Basingstoke. Today a general medical practice surgery in the town is named after this famous surgeon.

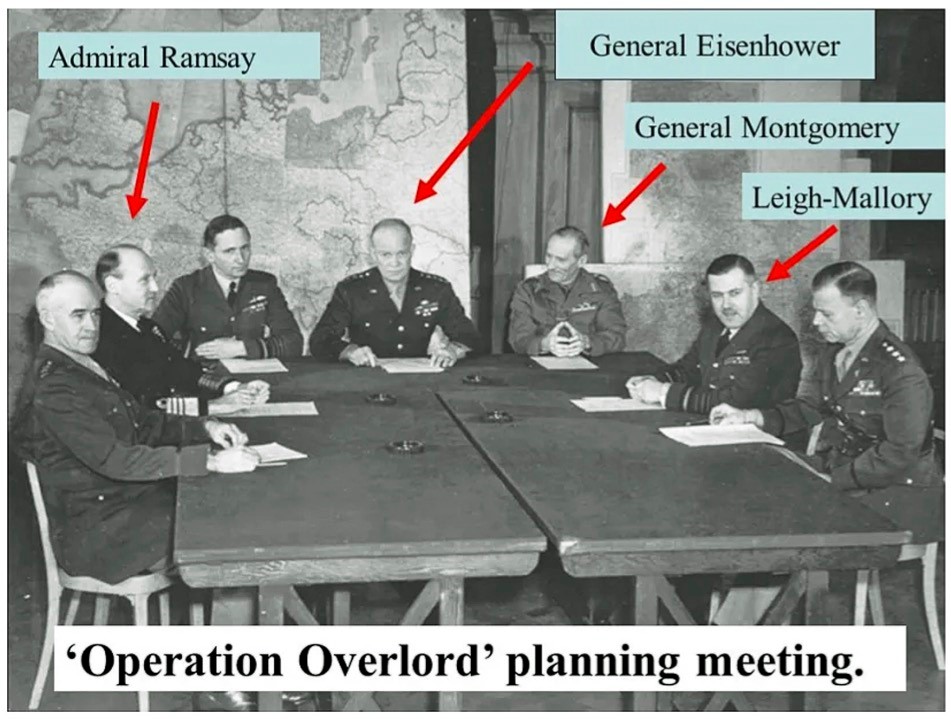

WW2 1939-45 saw further use of field surgical and transfusion units positioned as close as possible to the point of injury. But it was another medical officer, Alexander Fleming, who in 1943 developed the wonder drug, Penicillin, that became a game changer in recovery outcomes.

Post 1945 the helicopter became crucial to the recovery of battlefield casualties with the popular later TV programme, MASH, demonstrating the joined-up thinking with the connection of emergency evacuation with a mobile army surgical hospital during the Korean war 1950-53.

Helicopter use was necessary during the Falklands conflict of 1982 transferring casualties to hospital ships while the Afghan campaign 2001-2021, saw significant use of various helicopters in both the deployment of troops and casualty evacuation. Many casualties received medical support at Headley Court near Birmingham that become famous for the increasing use of prosthetics.

Peacetime also sees military services in demand under ‘hearts and minds’ policies both for medical and dentistry work in foreign countries. The Ebola outbreak in parts of Africa needed their intervention and at home the Covid-19 pandemic saw the construction of temporary hospitals.

2024 saw the amalgamation of three historical medical sections into one cohesive unit called the Royal Army Medical Service (RAMS). These were the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) founded in 1898, the Royal Army Dental Corps (RADC) founded 1921 and the Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps (QARANC) founded 1902. The aim is to provide full medical and dentistry services to our military for use in peacetime and during conflict to a level matching that of the NHS.

You must be logged in to post a comment.